“Plains Indian Women and Interracial Marriage in the Upper Missouri Trade, 1804-1868”

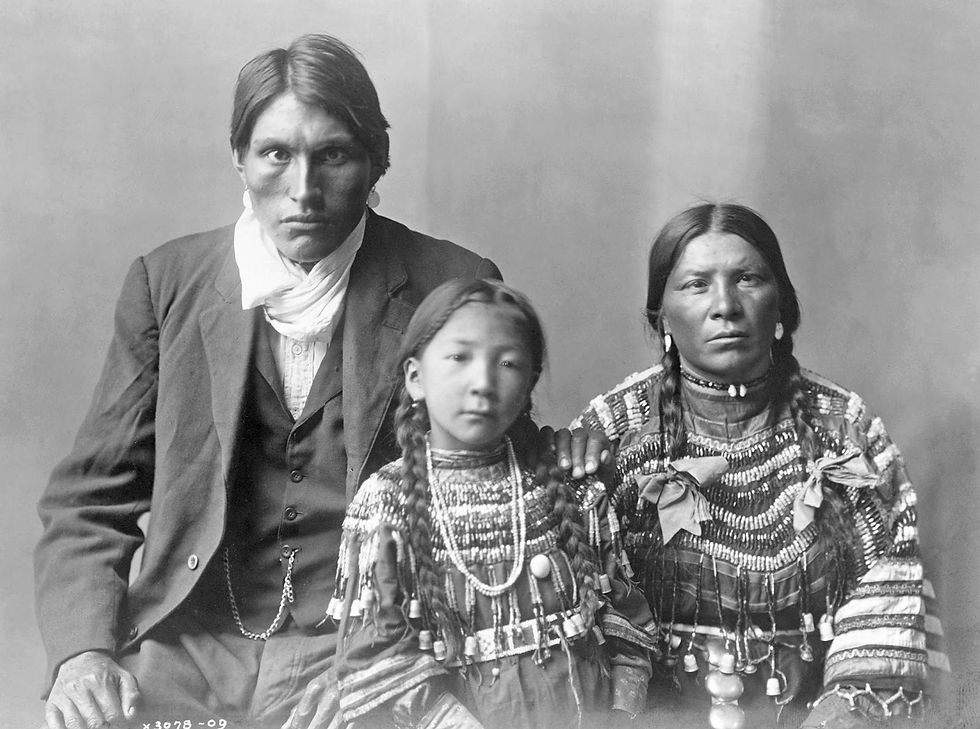

Michael Lansing’s essay “Plains Indian Women and Interracial Marriage in the Upper Missouri Trade, 1804-1868” details the integral role that interracial marriages played in successful trading between Europeans and Indians in the early- to mid-19th century on the Missouri River. As “mediators, economic informants, cultural transmitters, companions, producers, and consumers – all in the context of liaisons and intermarriage – Native women gained status in Indian and white eyes.” As “principle traders” they were both producers and distributors of trade goods, caretakers of an “intricate power relationship” that was a crucial role for them pre-contact, and, ultimately, “agents of change” helping to create “a new social context specific to the Upper Missouri trade that reflected aspects of both cultures.”

Lansing describes this complex role that native women held in Native societies offering the story of Lakota Wambdi Autepewin as a prime example. By the age of 28 Autepewin was situated at Fort Pierre in bourgeois society, the wife of a successful French fur trader. She and her husband had built a brisk business in the buffalo hide trade. Like other similarly situated women, the marriage to her European husband had given her “privileged station in Plains communities.” Her business acumen and other abilities gained her a reputation among government officials, and in 1868 she was instrumental in bringing the parties together when the Lakota Sioux and other area tribes negotiated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, securing the Black Hills. Native women leveraged interracial marriage to help their tribes adapt to the cultural onslaught that European traders brought to the Missouri River and as a strategy to lessen the broad impact of this societal upheaval that would change their lives forever.

“Touching the Pen: Plains Indian Treaty Councils in Ethnohistorical Perspective”

From 1851 to 1892, the Kiowa, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes signed a series of treaties with United States treaty commissioners, establishing boundaries, fishing rights, and other concessions. Ethnographer Raymond J. DeMallie has discerned that the plain language found in these treaties has features and characteristics that had the effect of “establishing the common humanity of white and Idnains, a moral base…from which to negotiate for concessions.” In his article “Touching the Pen: Plains Indian Treaty Councils in Ethnohistorical Perspective” DeMallie goes on to note that these features – “ritual aspects,” “recitation of both sides’ demands and requests,” and “distribution of presents” – were accompanied by tactical devices that were characteristic of the entreaties and include the strategic use of kinship terms and, on the part of Indians, the establishment of “an equivalence between Indians and whites to provide a moral basis from which to ask that Indians be treated the same as whites.” Together, DeMallie describes how studying the specific language, tactics, and characteristics of treaty council proceedings “allow some reconstruction of the Indians’ points of view as they were threatened with cultural extinction in the face of white American expansion.”

As an example, DeMallie points to the 1851 Treaty Council at Fort Laramie. There the Sioux, along with eight other bands of Indians living in Wyoming Territory signed a treaty establishing land boundaries and safe passage along the Oregon Trail. The building of tents and other private spaces, along with the orderly conduct of the meeting as “reciprocated …by holding dog feasts, warrior society dances, and displays of horsemanship,” a common ritualistic style of treaty councils. Later, during the proceedings, the Sioux and Arapaho differed on whether to deal with white people at all as all sides made various demands and requests. And the distribution of presents marked the conclusion of the treaty council negotiations, with one participant noting that it was a “standing rule” to give gifts among Indian tribes to gain influence. In another treaty council exchange in 1866 held in Kansas with the Kiowas, Chief White Bird “claims an especially close relationship with the sun,” using kinship terms to establish for his listeners an equivalency with the Great Father, a term used by negotiators to describe the President of the United States. The Great Father reference is also found in the treaty language from Fort Laramie. By making these comparisons and looking for commonalities such as characteristics and tactics like the ones found in treaties, ethnographers and historians alike can gain further insight into how Indian people adapted and framed their language when dealing with foreigners to protect their heritage, culture, and traditional living spaces from encroachment.

“’They Mean to be Indians Always’: The Origins of Columbia River Indian Identity, 1860-1885”

The Indians of the Pacific Northwest were some of the last tribes to encounter encroaching white settlers near the end of the 19th century. From 1860-1885 government officials undertook a campaign to “clear the land for settlers” but were confounded by the fact that, as “historically creat[ed]…labels,” many groups of indigenous people living along the Columbia River did not identify as neat political units such as “tribes” or “bands”. Additionally, their efforts were confounded by increasing numbers of “renegade” Indians that refused to live on reservations and regularly moved from location to location, sometimes raiding or hiding. In his article “’They Mean to be Indians Always’: The Origins of the Columbia River Indian Identity, 1860-1885” historian Andrew H. Fisher traces this opaque series of events that led one federal agent to remark of one errant resistor, “He means to be an Indian always, in the fullest sense of the character attached to that name.”

As the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) agents saw a rise in the number of these renegade Pacific Northwest Indians they began to “increasingly [view them as] …a coherent group bent on undermining federal authority and corrupting their reservation kin.” Indeed, as Fisher explains, federal authorities had successfully entreated with various groups, designated them, and tens of thousands of Indians along the Columbia had settled on to reservations, with many “defending their reservations…and com[ing] to value them as homelands.” A representative of the residents of Warm Springs, one Queahpahmah, intervened on behalf of one renegade called Hehaney who had refused to live on a reservation for years. Assuring authorities that Hehaney would see the value of the pastoral life that had been imposed on Indians newly transplanted to their reservations, he was rebuffed as Hehaney went on to resolve his dispute with federal authorities in a showdown in 1885.

Other expressions of the divide between reservation Indians in the Pacific Northwest and their renegade, or non-reservation kin, included spiritually inspired resistance movements. “Religion provided the ideological underpinning for renegade resistance and an incipient Columbia River Indian identity,” notes Fisher. When the Washaani, or ‘Dreamer Faith’ emerged, headed by respected priest Smohalla of the Wanapam village on the River, and offered for the faithful, through dancing, a vision of resistance that included “cast[ing] off white ways, reject[ing] the reservation system, and seek[ing] wisdom in dreams,” it proved to be of this type of unifying ideology, and federal officials reacted with predictable alarm. Nevertheless, their efforts were frustrated by the fact that Pacific Northwest people are proud of this heritage of “defiance” and have adopted the label ‘Columbia River Indian’ out of deference and respect to the men and women that agitated for Indian rights in the area and for those that continue to do so right up to the present day.

References

Nichols, Roger L. The American Indian: Past and Present. 6th ed. Norman, Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.